Anatomy of a Semiconductor Downcycle

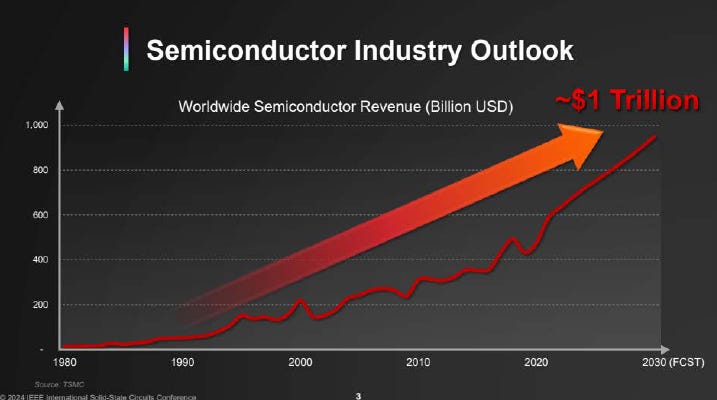

The boom bust cycle is baked into semiconductor and it’s what makes the industry so beautiful, brutal and never boring. Cycle has been around since the industry existed more than 70 years ago and a downcycle occurs every 3 to 4 years. What makes cycle different for the semiconductor industry is that believer of Moore’s Law knows the industry will always grow to new height. Yes, the semiconductor industry has weathered over 15 downcycles, yet it remains firmly on track to hit $1 trillion in revenue by 2030.

Source: TSMC

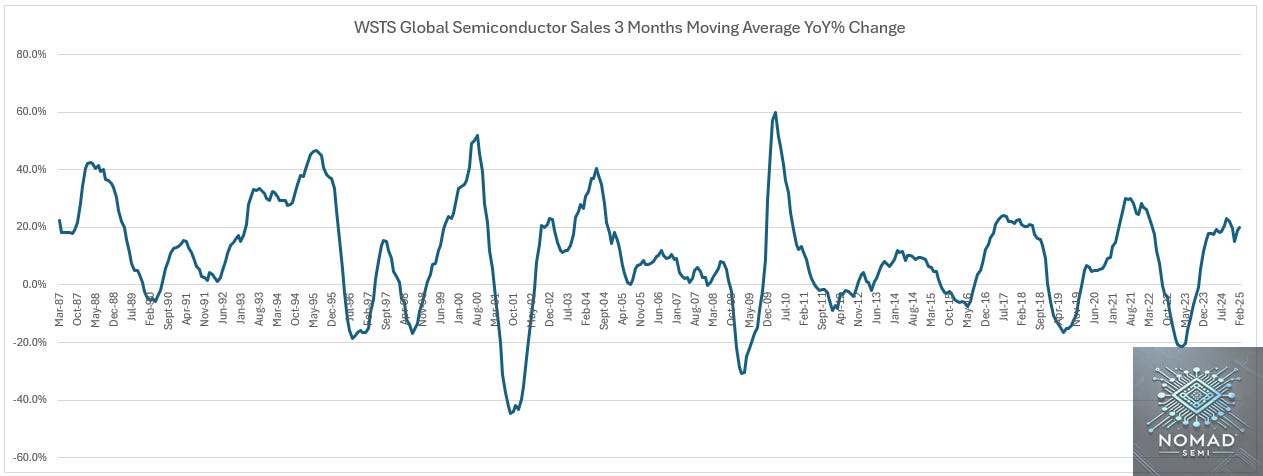

Source: World Semiconductor Trade Statistics

There are 2 different drivers of semiconductor downcycle, but they are inherently a mismatch of demand and supply. Supply is inelastic, while demand fluctuates a lot more.

The first is a capacity cycle where fabs have to make investment decision a few years ahead of mass production. During boom period, strong demand gives fab the confidence to invest for the long term structural growth drivers of the industry. Everybody makes the same decision and starts to regret the situation of overcapacity when their capacity come online at the same time. Capacity cycle is a lot less common post GFC given the high level of consolidation in the industry. It still happens for more fragmented segments such as analog (TI), power discrete and SiC substrate.

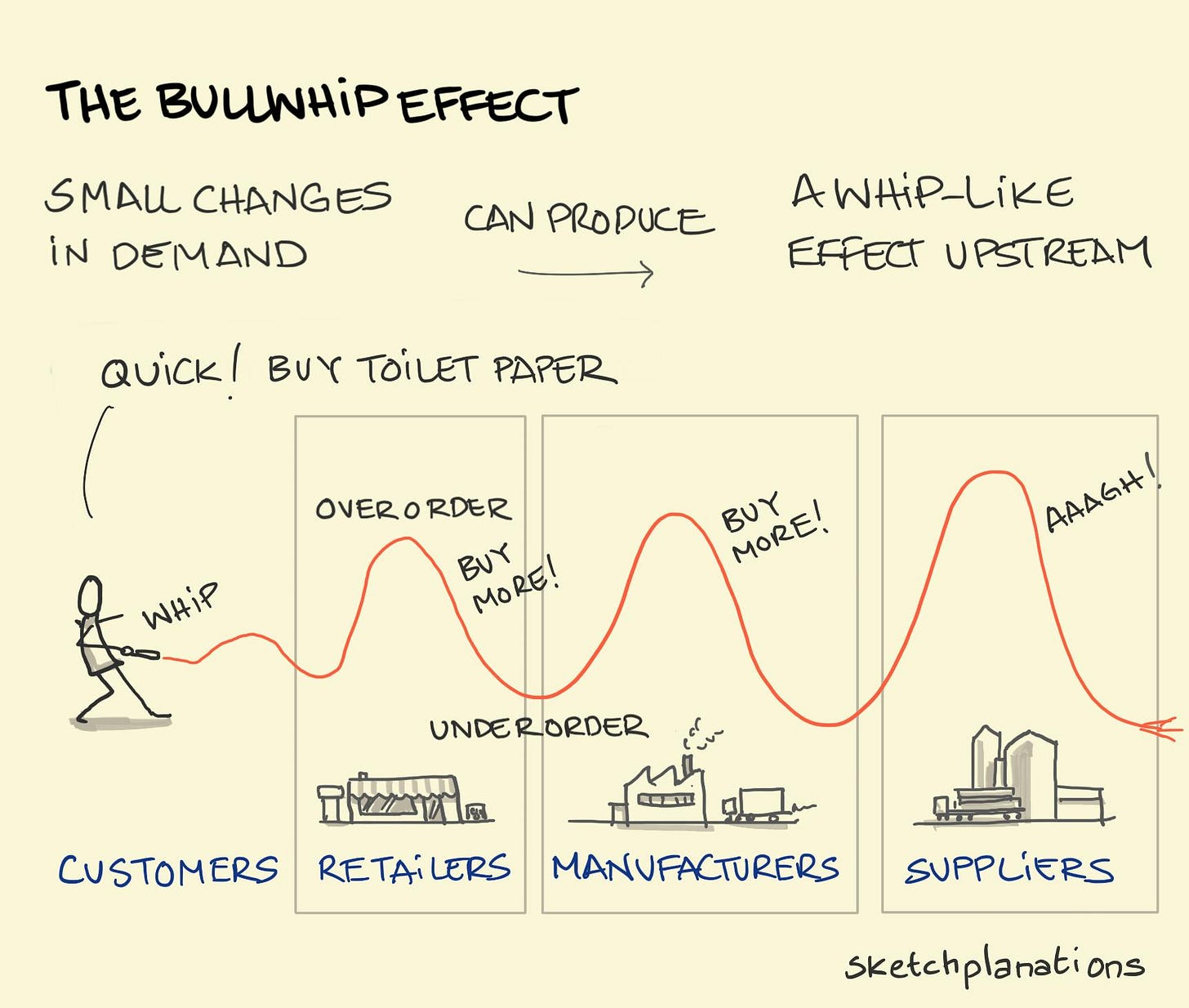

The second driver is the inventory cycle, which occurs more frequently than the capacity cycle. This is also known as the bullwhip effect, where small changes in end demand can lead to increasingly amplified swings in orders and inventory levels up the supply chain. During periods of rising demand, customers restock and rebuild inventory. In times of shortage (such as during COVID), this can also lead to double ordering. But when demand slows, customers cut back sharply to clear the excess inventory, causing a sudden collapse in new orders. An example is as such:

End demand changes slightly, for e.g. a 3% drop in smartphone sales

OEMs react conservatively, cutting chip orders by 7% to adjust inventory.

Distributors pull back more, fearing excess stock and cut orders by 15%.

Foundries see a sharp drop, leading to lower utilization rate and margin pressure.

Source: Sketchplanations

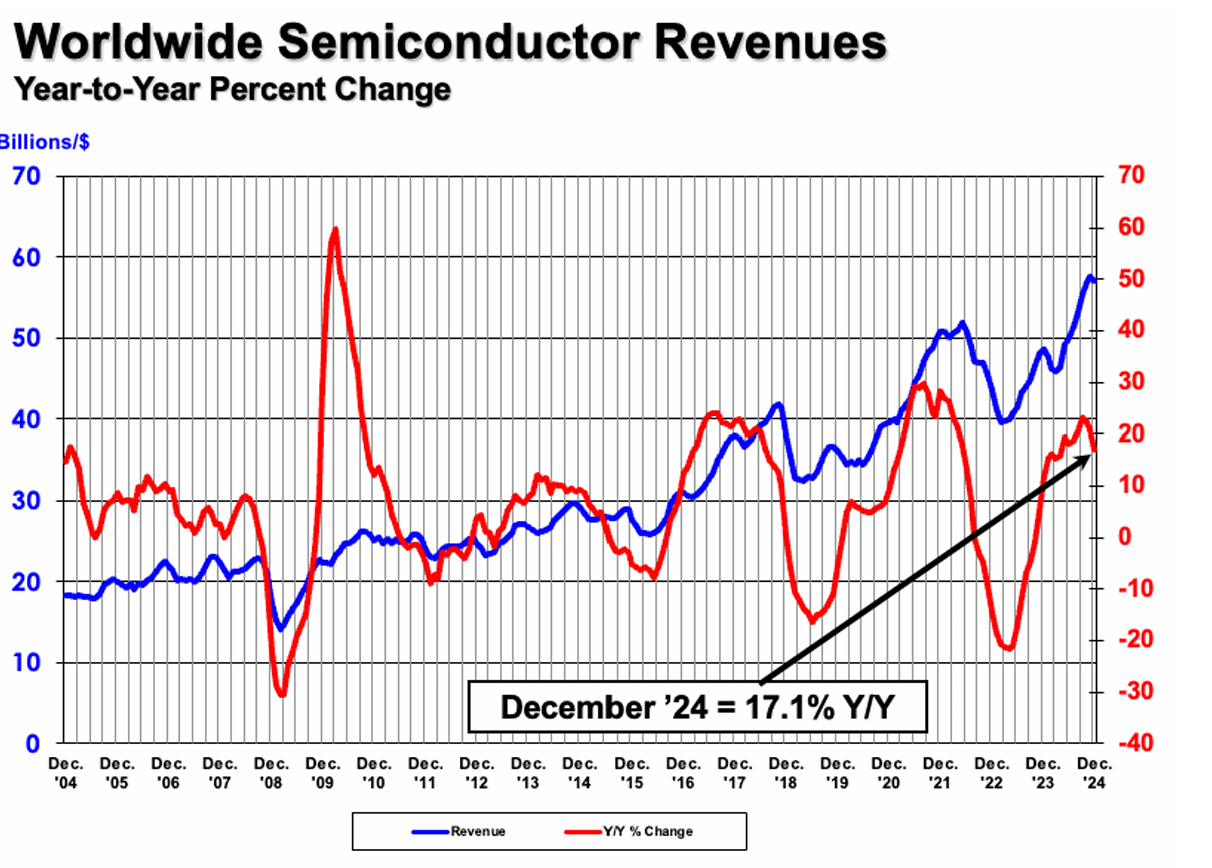

A downcycle occurs when global semiconductor sales growth peaks and begins to decelerate (i.e. January 2018 and December 2021), triggering an inventory correction across the supply chain. Once sales growth peaks, it often has a tendency to swing hard towards flat or negative region.

Source: WSTS Global Semiconductor Sales from 1987 to 2025

While situation is still fluid, we are likely approaching the next downcycle in a few months based on the latest tariff development. My prediction is that global semiconductor sales growth will peak in Q3 2025 for the following reasons:

U.S. tariff leads to demand shock

Pull forward demand

AI: Inventory correction and softer capex growth in 2026

U.S. Tariff Leads To Demand Shock

On 2nd April 2025, President Donald Trump declared "Liberation Day" unveiling a sweeping tariff regime aimed at reshaping global trade dynamics. Invoking a national emergency, he imposed a universal 10% tariff on all imports, with significantly higher "reciprocal" tariffs targeting specific countries: 34% on China (raising the total to 54%), 32% on Taiwan, 25% on South Korea, and 20% on the European Union, among others. The announcement triggered immediate global backlash and market turmoil. China retaliated with tariffs of up to 125% on U.S. goods, while the current tariffs on China stands at 145%.

Source: CNN

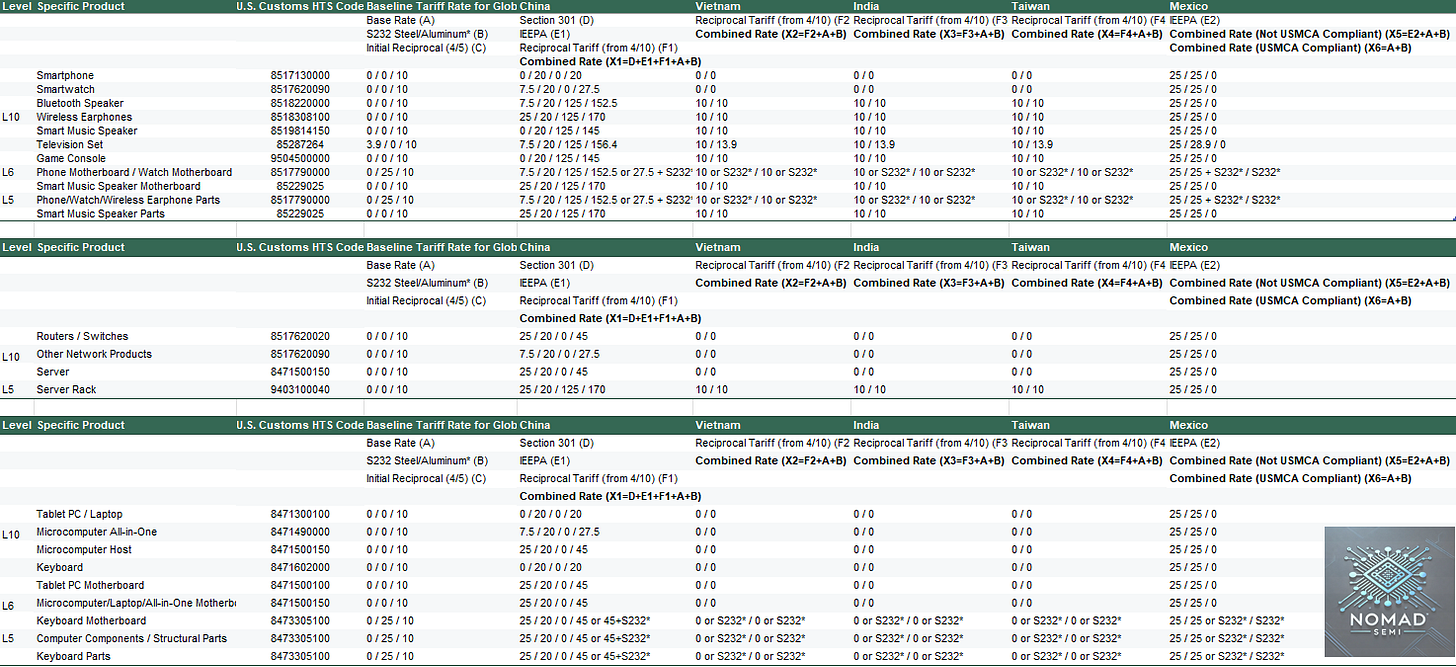

On 9th April, the Trump administration signaled potential exemptions and a 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs to facilitate trade negotiations, though the tariffs on Chinese imports remained in effect. Few days later, it was revealed that the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency has exempted certain electronics products such as smartphone, PC, network equipment from reciprocal tariff. As it stands today, these are the current tariff rate according to Foxconn:

Source: Foxconn

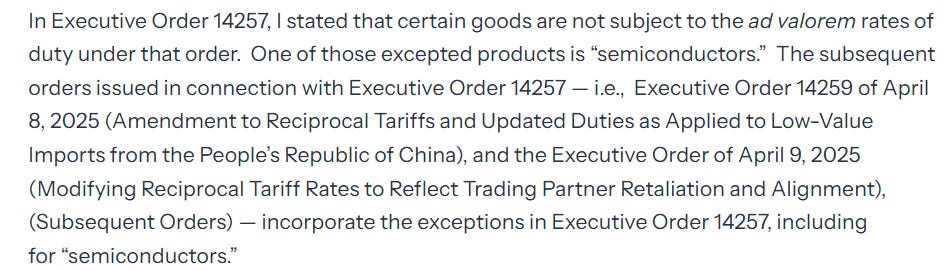

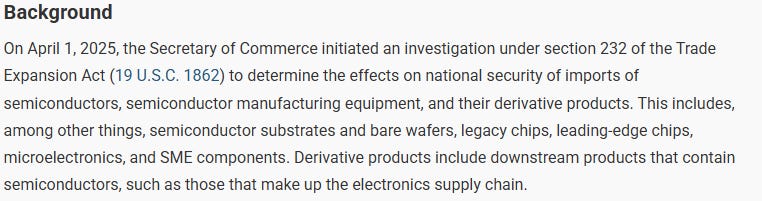

However, this is not over yet as the reciprocal tariff exemption is merely shifting these electronics product to be evaluated under a separate semiconductor tariff. On 14th April, it was revealed that the Department of Commerce has launched a probe on semiconductor tariff under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. Therefore, it is highly likely that semiconductor and electronics products will be subjected to a future tariff irrespective of the deals that countries may have struck with President Trump. We know that as steel, aluminum and automotive have been subjected to Section 232 duties even if they are from Mexico or Canada.

Source: White House

Source: Federal Register

Tariffs directly influence demand by altering prices, compelling companies to either pass increased costs to consumers or absorb them. As prices rise, demand typically declines, adhering to the law of demand. The extent of this impact on semiconductor varies across different verticals.

Source: Economics Help

Personal Computers (PC): The U.S. accounts for approximately 25% of global PC unit sales and 30% of PC value sales. Margin for PC OEMs is low, which will force them to pass on higher cost to the end consumers. In addition, 80% of global notebook assembly capacity is located in China, where China will slap a 125% tariff on Made-in-USA Intel chip and U.S. will slap another layer of tariff on China imported PC. This makes PC the most vulnerable vertical to tariff. Most of the OEMs do not plan to set up assembly plant for PC in the U.S. and have decided to further expand their capacity in ASEAN.

Smartphones: The U.S. represents about 10% of global smartphone unit sales and 20% of value sales. However, U.S. is 40% of Apple’s sales as it holds more than 50% market share in the country. This makes Apple more vulnerable than Android smartphone, which is not a good news as iPhones tend to have much higher semiconductor content than the average Android smartphone.

Servers: Server demand has less direct impact from the tariff as the ODMs have plenty of capacity in Mexico and U.S. TSMC’s Arizona Fab 21 has started mass production of 4nm, which is precisely the node that Blackwell is made.

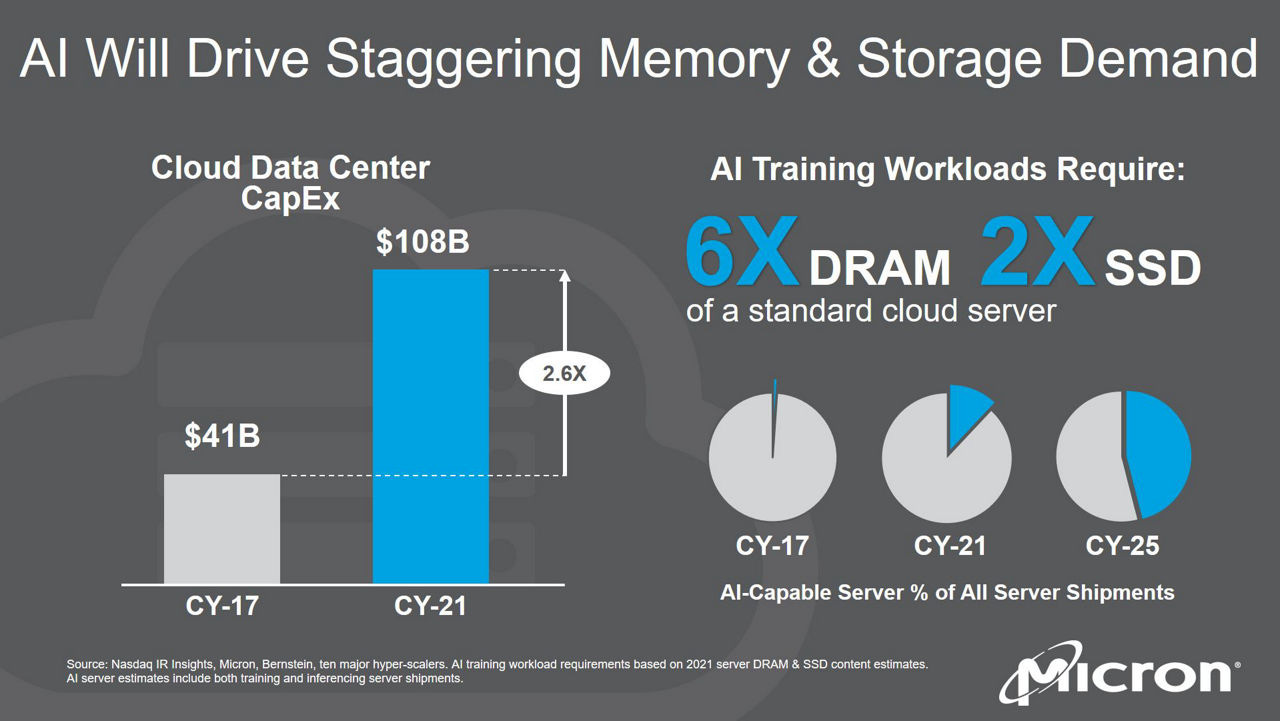

Memory: Most of the memory manufacturing sites are located outside of U.S. in countries such as Korea, Japan, Taiwan and Singapore. Many of the memory modules and SSDs are also assembled outside of U.S. Even for Micron, they relied heavily on their NAND factory in Singapore and DRAM factories in Taichung & Japan. Their new Idaho fab will only contribute meaningful supply in 2027. Price elasticity for memory (especially NAND) is high which should lead to lower demand.

Pull Forward Demand

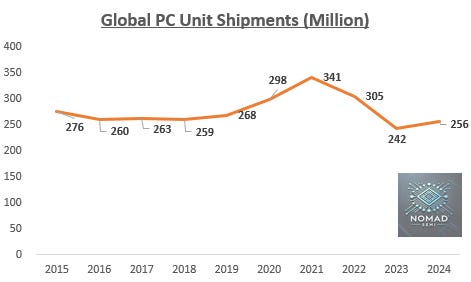

Pull forward demand is bad for semiconductor as it creates a high base and leads to lower demand in the future. An example is the elevated PC annual sales of >300 million units during the Covid period of 2020 to 2022, above the historical average of 260 to 270 million units. In 2023, PC shipment fell by 15% YoY to 242 million units, which is the lowest unit shipment since 2006. From the peak in 2021, unit shipment fell by 30% in 2 years.

Two sources of pull forward demand have emerged, which will put pressure on sales in 2026.

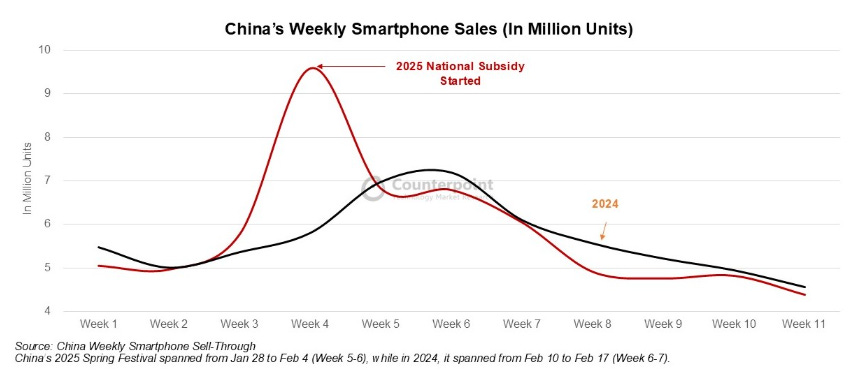

China consumer electronics subsidies

On January 20, 2025, China officially launched a national subsidy program for smartphones, tablets and smartwatches. The government offers a 15% discount on smartphones priced below RMB 6,000, capped at RMB 500 per device. This initiative aimed to stimulate consumer electronics demand and was part of a broader effort to boost domestic consumption. Notably, some provinces, such as Jiangsu, had already implemented similar subsidy programs as early as November 2024. The subsidies led to a significant uptick in smartphone sales. In January 2025, China smartphone sales grew by 17% YoY and 41% MoM to 29 million units. Combining with February, China smartphone sales grew by 13% YoY. Total Electronics & Appliances sales in China grew 35.1% YoY in March.

Source: Counterpoint Research

Tariff induces pull forward demand during the 90-day pause

Following President Trump's announcement of sweeping tariffs on imports, a 90-day pause was granted for most countries, excluding China, to allow for negotiations and adjustments. This temporary reprieve prompted both businesses and consumers to accelerate purchases of goods, particularly high-value electronics, to avoid potential price increases once the tariffs were reinstated.

Above seasonal sales strength has been seen across multiple verticals. U.S. new vehicle sales grew 4.8% YoY in Q1. According to IDC, global PC sales grew by 5% YoY in Q1 of which Macbook sales grew by 14% yoy. These are Q1 sales where the world is not aware of the big tariff spike. Post Liberation Day, panic buying should have accelerated especially with the 90-day pause.

Source: Apple

For corporates, the 90-day pause is the best opportunity for them to stock up on electronics before reciprocal tariff resumes or Section 232 tariff is implemented for semiconductor. Reuters reported that Apple had airlifted 600 tons of iPhones from India to beat the tariffs. Morgan Stanley raised their Q2 iPhone build by 10% to 45 million units, which is 5 to 15% higher than typical seasonality (destocking to prepare for the new iPhone model in September).

Notebook shipment by the ODMs in Q1 grew 3% YoY, which is 10% higher than seasonality. In particular, notebook shipment in March grew by 39% MoM. In fact, ODMs have already started to prebuild inventory since November after President Trump won the election. Both AMD and Intel have seen double digit growth for PC CPU shipment in Q4, which is much higher than flattish PC unit shipment.

Despite elevated channel inventories, retailers and distributors are seizing the opportunity to stock up on tariff-exempt smartphones and PCs during the current reprieve. This is a temporary window of opportunity to secure inventory at lower costs. However, even if tariffs are eventually lifted, the accumulation of high channel inventory typically leads to a subsequent destocking phase.

AI: Inventory Correction, Softer Capex outlook and Geopolitical risk

Inventory Correction

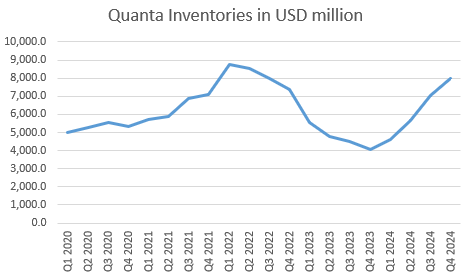

By now, most should be familiar with the issues plaguing GB200 rack deliveries. GB200 server rack production is currently facing significant challenges due to assembly yield issues, particularly at the ODM level (Foxconn, Quanta, Wiwynn). The complexity of the GB200 NVL72 systems, which integrate 72 GPUs and 36 Grace CPUs per rack, has led to difficulties in the assembly process. These challenges have resulted in lower than expected rack shipment volumes, with estimates for 2025 reduced from an initial 50,000 racks to approximately 15,000 racks. GB300 is also facing assembly yield issues as delivery timeline has been pushed to Q1 2026.

Despite ongoing assembly challenges with NVIDIA's GB200 racks, NVIDIA's revenue outlook for the first half of 2025 remains robust. This resilience is largely due to NVIDIA's revenue recognition policy, which records sales upon the shipment of GB200 boards to ODMs, rather than upon the final delivery of assembled racks to end customers. Consequently, delays in rack assembly have led to an accumulation of inventory at the ODMs, without immediately impacting NVIDIA's reported revenues. TSMC has been shipping out Blackwell since November while the ODMs revenue growth has lagged. The true extent of inventory build will only be known when the ODMs report their financials over the next few quarters.

However, this inventory buildup is unsustainable for the ODMs. Operating on thin margins and facing significant working capital requirements (given the high value of GB200 components), ODMs are under financial strain. To manage these pressures, many have resorted to funding strategies such as issuing convertible bonds and GDRs to bolster their capital in 2024. Wistron is in the plan to issue 250 million new shares in GDR. While these measures provide temporary relief, the continued accumulation of unsold GB200 inventory could lead to ODMs deciding not to increase their GB200 inventory. This is perhaps why CoWoS demand forecast has been revised down. If rack delivery issues remain unresolved, there will eventually be wafer order cut from Nvidia.

Weaker sales outlook for FAMG and elevated capex intensity

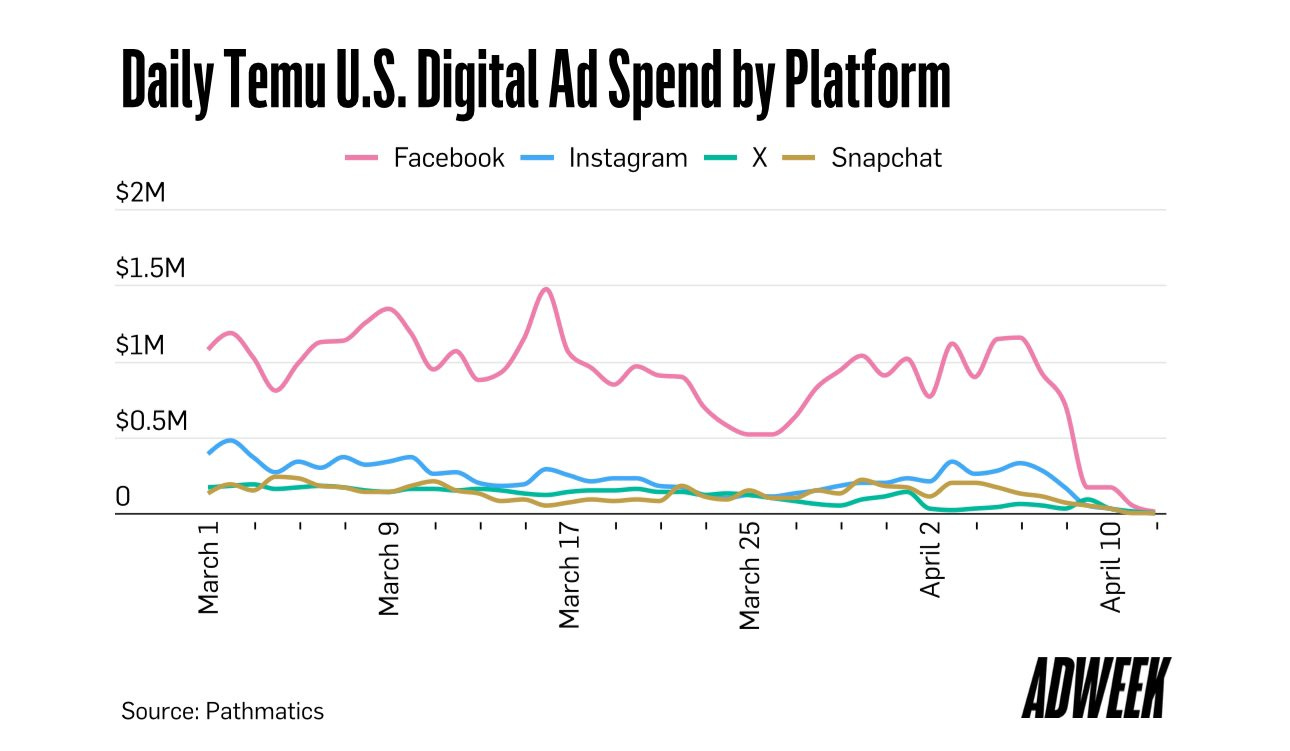

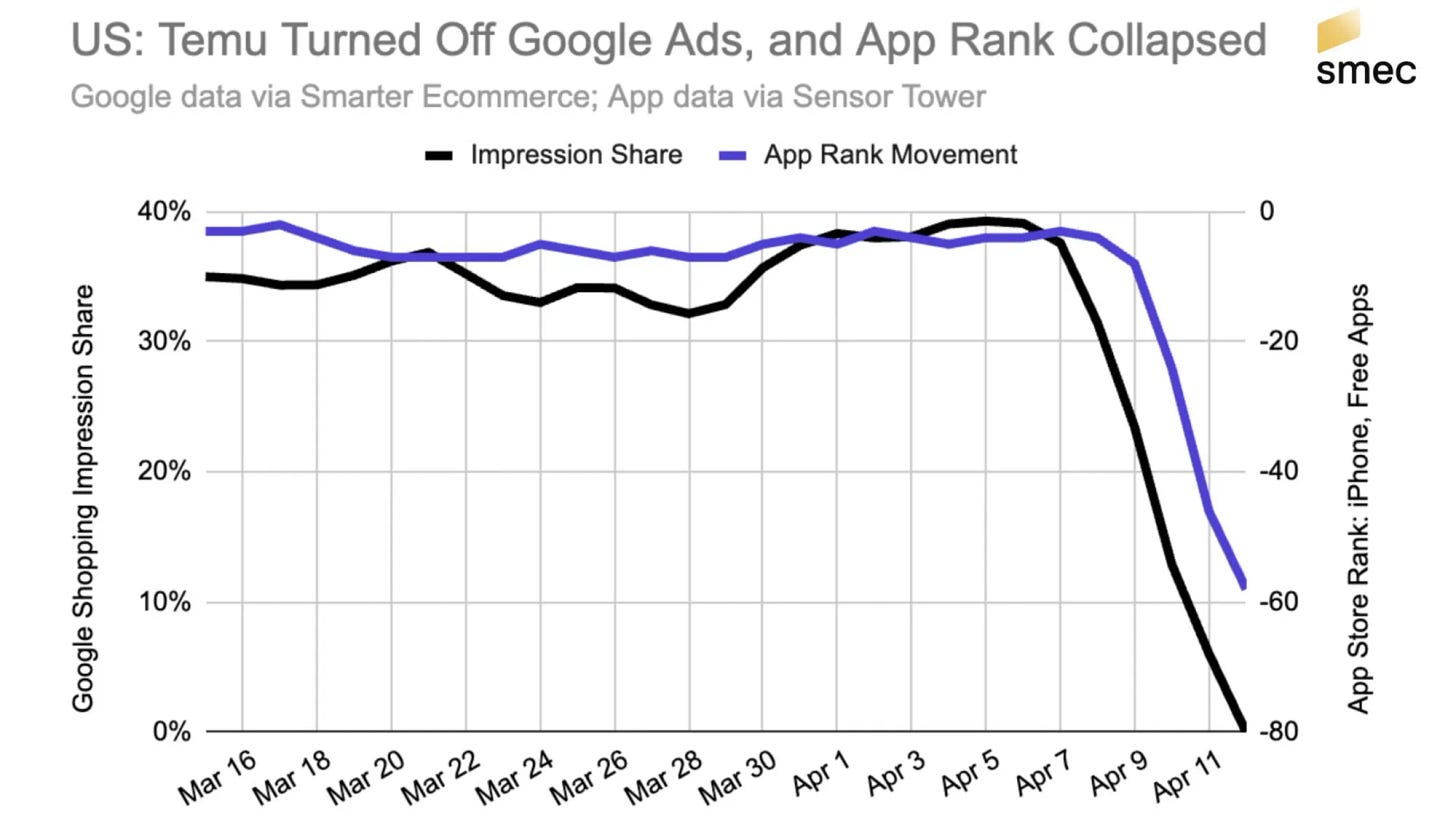

The ongoing trade war does not bode well for companies such as Meta, Amazon and Alphabet. Meta and Alphabet are heavily reliant on advertisement sales which is highly correlated to the state of the economy. Both Temu and Shein have significantly reduced their advertising spend on Google and Meta platforms. Meta’s share price has since declined more than 33% from its February peak. Meanwhile, over 50% of Amazon’s third-party sellers are based in China, highlighting the platform’s exposure to the ongoing trade war between China and U.S.

Source: Adweek

Source: SMEC

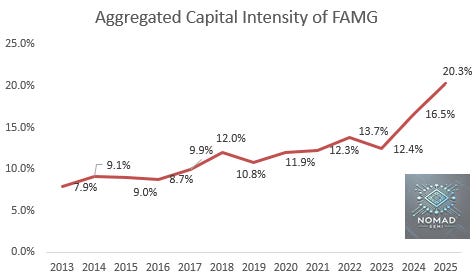

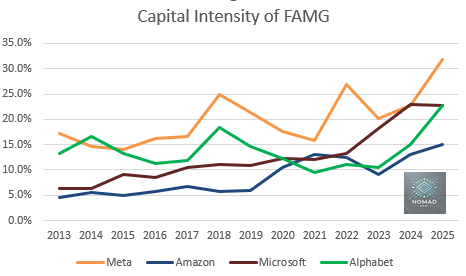

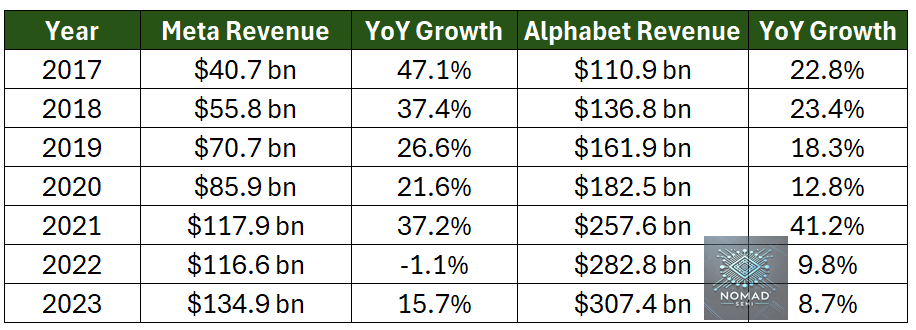

Capex intensity (capex-to-sales ratio) is now at an all-time high, putting pressure on free cash flow. FAMG are expected to spend 50-70% of their operating cash flow on capex in 2025. Capex can rise either through revenue growth or higher capital intensity. In 2024 and 2025, the sharp spike in capex spending by the FAMG has led to a notable decline in free cash flow. Historically, during periods of economic uncertainty or slower growth, the FAMG have responded with inventory digestion or capex moderation, as seen in 2019 and again in early 2022.

Before ChatGPT’s breakout in late 2022, there was an earlier wave of AI enthusiasm sparked by AlphaGo’s 2016 victory over Lee Sedol. During that period, shares of SK Hynix and Micron surged over 300% from 2016 to their 2018 peak, while Samsung had already begun mass production of HBM.

Source: Micron in 2018

In 2019, a slowdown in revenue growth prompted capex reductions across the FAMG group. This also coincides with the trade war that President Trump started in his 1st presidency. Meta cut its capex guidance twice, lowering it from an initial $18–20 billion to $16–18 billion, as sales growth decelerated due to user saturation in the U.S. and the impact of GDPR in Europe. Alphabet also saw a significant moderation in capex following its slowest quarterly sales growth since 2015. For Microsoft, capex growth moderation reflected a digestion phase after heavy infrastructure investments in the past 2 years.

In 2022, FAMG cut capex in response to a sharp slowdown in revenue growth and rising macroeconomic uncertainty. Soaring inflation, interest rate hikes, and weakening consumer demand prompted a shift from aggressive expansion to cost discipline. Meta and Alphabet scaled back infrastructure and hiring plans, while Microsoft and Amazon focused on optimizing existing capacity after years of elevated investment during the pandemic driven digital surge.

While the FAMG have committed to their capex plans for 2025, the announcement of Liberation Day has reintroduced uncertainty into the economic outlook. Any meaningful hit to revenue growth could lead to a moderation in capex expansion in 2026. Long-term investment in AI remains intact, driven by the continued validity of the 3 Scaling Laws. However, digestion periods like those seen in 2019 and 2022 can still occur, even in the presence of transformative technologies like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and Scaling Law (Kaplan, 2020).

Geopolitical risks and regulations

There are also additional geopolitical risks such as the recent ban of NVIDIA’s H20 shipment to China. NVIDIA has to take a $5.5 billion charges with revenue impact of at least $10 billion. In January 2025, the Biden administration introduced the AI Diffusion Rule, a comprehensive export control framework aimed at regulating the global distribution of advanced U.S. AI technologies. AI Diffusion Rule is set to be take effect from 15th May 2025 if it is not reversed by the Trump administration. This will have a big impact on GPU demand coming from Sovereign AI across Asia and Middle East.

Silver Lining In The Dark Cloud

While the dark cloud has gathered, several factors suggest that we do not have to be overly pessimistic of semiconductor companies. This is because market always looks forward for semiconductor stocks. To put it in another way, semiconductor stocks often bottom ahead of the bottom in semiconductor sales growth.

The market has partially priced in a certain degree of downcycle

In past upcycles, share price corrections typically occurred only after global semiconductor sales growth peaked and began to decline. This time, however, SOXX peaked early in July 2024, even as the 3-month moving average of global semiconductor sales growth has remained elevated.

The current 37% drawdown in SOXX is already approaching the 49% seen during the 2022 downcycle. While historical drawdowns aren't always directly comparable, it's worth noting that the sector saw much deeper declines of 60-70% following the Dot-Com Bubble and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Conversely, corrections were more modest at more than 30% during the 2018 and COVID downturns, when macroeconomic conditions were relatively more benign.

Asynchronous cycles across semiconductor verticals

What makes this cycle unique is the lack of synchronization across semiconductor verticals. Smartphones, PCs, and memory were the first to correct in 2022 and also the first to rebound in 2023. The strength of the current upcycle has been driven almost entirely by AI related demand, while most other end markets remain sluggish. Notably, automotive semiconductor companies are still working through inventory corrections nearly three years after SOXX peaked in December 2021! It is more appropriate to say there are multiple cycles within the different verticals.

This means that certain segments may bottom earlier than others. Using peak-to-trough drawdowns as a guide, semiconductor equipment companies have seen declines of 40–50%, driven largely by concerns over their China revenue exposure. Lower valuations are a positive for semicap, as the Big Four allocate a significant portion of their free cash flow to do share buybacks. Meanwhile, share prices of analog semiconductor companies are approaching their 2023 lows, reflecting their high sensitivity to weakness in global industrial and automotive demand although they are already under-shipping actual demand.

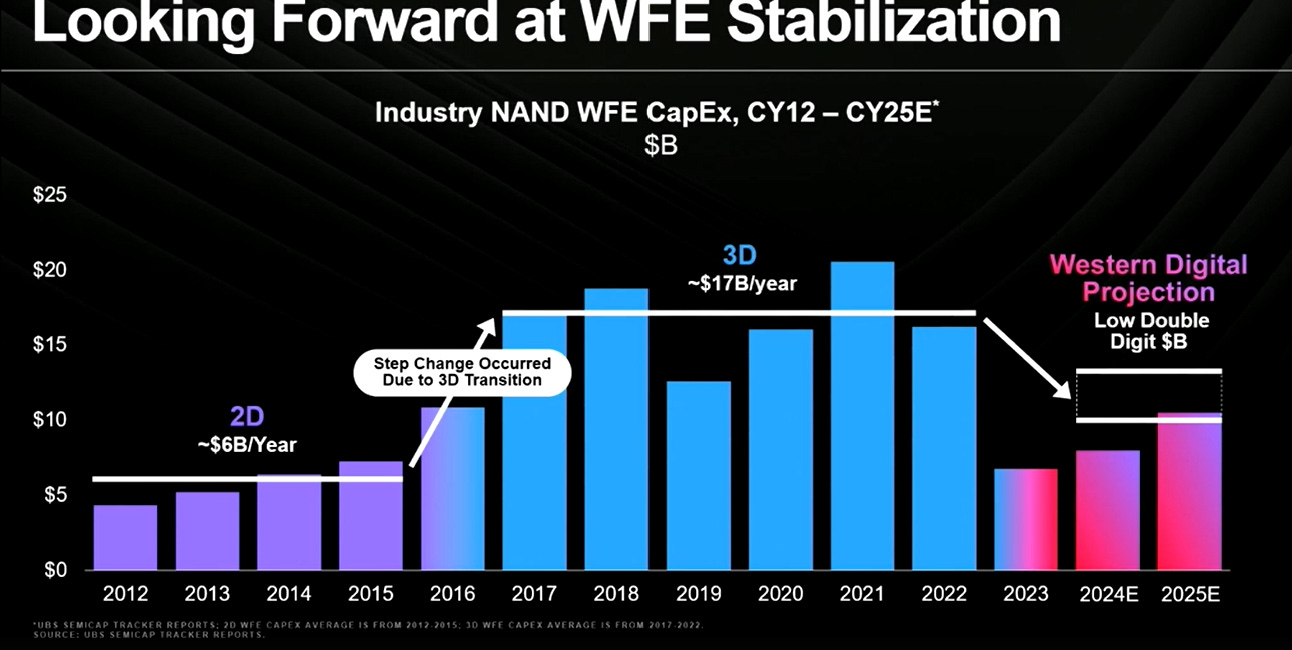

2025 WFE outlook

As major memory and logic customers have reported their results, it is time to revisit the outlook for WFE (Wafer Fabrication Equipment) in 2025.

On the other hand, AI related stocks have slightly outperformed the broader SOXX drawdown, with shares of Broadcom, NVIDIA, and TSMC declining around 33%. Historically, however, it’s often the hottest theme of the upcycle that faces the sharpest correction in a downcycle. Again, think about the carnage for automotive semiconductor companies after the 2021 shortage cycle.

In both the 2018 and 2022 downcycles, NVIDIA’s share price fell over 60% from its peak. Jensen has historically opted for steep inventory charges over price cuts, an action that has often marked the bottom in NVIDIA’s share price in 2019 and 2022. While the $5.5 billion charge helps to clear the Hopper inventory risk, we need inventory charge on Blackwell.

Meanwhile, TSMC’s ADR is still trading at a 15% premium to its Taiwan listed shares (2330.TW). The gap narrowed to nearly 0% at the stock’s bottom in Q3 2022. TSMC has just reaffirmed its full-year guidance for 2025, but is it a bottom when the world’s most important foundry hasn’t even cut guidance yet? We have also not seen any downward guidance revision from Broadcom and NVIDIA.

A slowdown in AI capex poses significant challenges for DRAM manufacturers. HBM3, for instance, consumes approximately three times the wafer capacity of DDR5 owing to its larger die size and lower yield rates . This shift has led companies like Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron to allocate more wafer capacity toward HBM and reducing the available supply for DDR5. The recent U.S. export ban on Nvidia's H20 AI chips to China is expected to reduce their revenue by about 1%, but it could lead to a 3% increase in DRAM bit supply as wafer allocations revert from HBM back to standard DDR5 module . This reallocation may exacerbate oversupply issues in the DRAM market, potentially impacting pricing and profitability for manufacturers.

Investment thesis for AI is intact as Scaling Laws remain

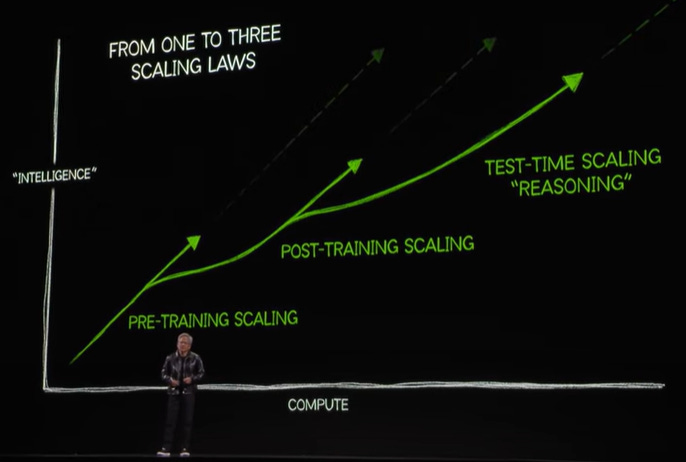

Today, we have three Scaling Laws in AI: Pre-Training Scaling, Post-Training Scaling, and Test-Time Compute Scaling. While Pre-Training Scaling may be nearing its limits in a few years, the latter two remain highly promising. As models grow, emergent properties continue to surface which reinforces the case that more compute remains a viable path to breakthroughs in AI capabilities.

Source: Jensen Huang at CES 2025

This dynamic also feeds into Jevons Paradox: as AI becomes more powerful and cost-efficient, its utility rises, spurring even greater usage rather than reducing demand. The emergence of AI agents further amplifies this trend, as their ability to automate tasks, generate outputs, and interact with other systems autonomously creates exponential demand for inference compute. AI agents are expected to improve significantly and achieve adoption readiness by the end of the year. The long-term investment thesis for AI remains intact, as it has since 2016. However, this doesn't preclude painful digestion periods like those seen in 2018 and 2022 from occurring along the way.

Conclusion

The semiconductor industry is no stranger to cycles and that’s exactly what has captivated me so deeply. Its inherent cyclicality is driven by capacity mismatches, inventory imbalances and unpredictable demand shocks. While the current cycle is shaped by unprecedented geopolitical developments, AI driven optimism, and asynchronous recoveries, it echoes the same dynamics that have defined the past 70 years.

As we head into what appears to be another downcycle, investors must brace for further turbulence while keeping their eyes on the long arc of technological progress driven by Moore’s Law. The road to $1 trillion in semiconductor industry revenue by 2030 will not be linear, but it is a path worth navigating. Lower valuations and falling share prices are often healthy first steps toward an eventual bottom.

For investors, the best way to prepare for the coming semiconductor downcycle is to stay focused on high-quality companies positioned to benefit from strong structural tailwinds once the industry recovers. If you find the content is useful, do subscribe to discover global semiconductor leaders worth owning for the next cycle.